-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Katherine Butler, Death songs and elegies: singing about death in Elizabethan England, Early Music, Volume 43, Issue 2, May 2015, Pages 269–280, https://doi.org/10.1093/em/cav002

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Music and death were closely linked in the Elizabethan imagination: harmony provided a link between heavenly and earthly life, while death was portrayed as an inspiration for eloquent song or, conversely, the silencing of life and de-tuning of society. The Reformation, however, brought profound changes to the theology of death and the associated functions of music. As opportunities for musical mourning and commemoration within the liturgy decreased, the significance of non-liturgical song for expressing grief in public or commemorating the dead intensified.

Considering first the 1560–70s fashion for death songs in the plays of the choirboy acting companies, and second, the growing trend for sung elegies in the 1580s, this article explores the role of non-liturgical song in representing and responding to death in Elizabethan England. The theatrical death songs mirrored the mythological swan’s song, representing an outpouring of eloquence in the face of impending death that played on conceptions of music’s ability to act as a liminal space between earth and heaven. The elegies were responses to actual bereavement and reveal how music provided both the medium and the imagery to express the experience of loss and disorder, or to create acts of consolation or remembrance. Though the Reformation influenced the prevalence of elegies and shaped responses to death within them, Catholic and Protestant elegies still shared both musical imagery and tendencies towards moralization and memorialization, despite their theological differences. These genres illustrate the musical creativity inspired by death and the social significance of song in fashioning responses to bereavement.

For the anonymous author of The Praise of Music (1586), death was ‘the dissolution of nature, and parting of the soul from the body, terrible in itself to flesh and blood, and amplified with a number of displeasant, and uncomfortable accidents as ... howling, mourning and funeral boughs’.1 Yet even in this time of fear, destruction and grief, music had its place. Music and death were closely linked in the Elizabethan imagination: harmony provided a link between heavenly and earthly life, while death was frequently portrayed as an inspiration for eloquent song or, conversely, the silencing of life and the de-tuning of society.

The Reformation, however, brought profound changes to the theology of death and the associated functions of music. Protestant views of the afterlife envisaged the soul going straight to either heaven or hell. With the denial of purgatory, the destiny of the soul lay with God and there was nothing more that the living could do. The result was that bell-ringing, intercessory prayers and Masses for the souls of the dead (said or sung) were regarded as futile.2 Or at least, this is what reformers were aiming for.

In practice the situation was far less consistent. It was not just that Catholics continued to worship in secret, holding their burial services at night to gain access to parish churchyards.3 Changing attitudes among congregations towards purgatory and intercessory prayer took time. People clung to old traditions at times of death, and visitation records complained of the continuing use of crosses, crucifixes, bells and other supposedly superstitious traditions.4 Even the Book of Common Prayer still maintained echoes of the Catholic rite in its burial service, borrowing some antiphons and responds.5 Other publications printed under royal licence also presented a confusing picture. In 1560 the Latin prayer book produced for university and college chapels still included a communion service for use at funerals (removed by the 1572 edition), while the Elizabethan primer of 1559 (reprinted as late as 1575) included a dirige with prayers for the dead.6

Catholic liturgy for the dead also had a continuing musical influence. In the 1560–70s Robert Parsons and William Byrd both set three responds from the Catholic Office of the Dead, inspired by those of their fellow court musician Alfonso Ferrabosco. Parsons’s Peccantem me quotidie and both composers’ settings of Libera me, Domine, de morte aeterna even included the plainsong as a cantus firmus, though as they set the whole text polyphonically, including the solo intonation, it is unlikely that they were intended for liturgical use.7 Byrd’s respond motets were published in the 1575 Cantiones sacrae dedicated to England’s Protestant queen, yet Catholics came to view these as sanctioned devotional dirges.8 Many compilers of music manuscripts copied Catholic music regardless of their own religious beliefs, so these respond motets too could be sung domestically by educated musical amateurs of both persuasions.9 Aside from their links with Catholic liturgy, the topics of the respond texts—Christ’s resurrection and God’s forgiveness of sins—could be pertinent to both Protestants and Catholics, despite the different theological significance for each. Indeed another of Byrd’s motets related to the liturgy for the dead, Audivi vocem, used a text common to both Vespers for the Catholic Office of the Dead and the Anglican burial service.10

Despite the continuities in practice and private belief, the stripping back of funeral services, the attempted prohibition of prayers for the dead and the ending of week, month and year’s minds (remembrances) reduced both the consoling effect of ritual and the public opportunities to mourn and commemorate.11 The role of music also lessened, though some Protestants still might desire the singing of a psalm, while for the nobility music remained a component in creating an impressive funeral befitting the status of the deceased. Thomas Morley composed a full set of funeral sentences, while John Dowland’s 1597 Lamentatio Henrici Noel set four penitential psalms and three hymns that may have been extra-liturgical music associated with the funeral of the courtier, Henry Noel.12 Nevertheless, music’s significance in the funerary ritual of parish churches shifted towards adornment of the service and edification of the mourners.

Other practices developed to take the place of intercessory rites, including funeral sermons, and the increasing use of memorial poetry and song outside the church.13 Such songs built on a longer, pan-European elegiac tradition including such notable examples as Franciscus Andrieu’s setting of Eustache Deschamps’s Armes, amours / O flour de flours commemorating Machaut, Josquin’s Déploration sur la mort de Johannes Ockegham or Isaac’s Quis dabit pacem populo timenti? for Lorenzo de’ Medici.14 As the singing of Masses for the soul was removed from parish church worship, the significance of non-liturgical song for publically expressing grief or commemorating the dead intensified, and was deployed by Catholics and Protestants alike.

These non-liturgical songs are the focus here. Freed from the prescriptions of church ritual and combining both religious and secular attitudes, they offer significant insights into the importance of music in representing and responding to death in Elizabethan England in ways that could transcend as well as reveal theological divisions. The musical elements within Elizabethan conceptions of death are considered first through the 1560–70s fashion for death songs in the plays of the choirboy acting companies, and second, via the growing trend for poetic epitaphs that sparked a concurrent interest in sung elegies for the deceased.15 These two genres illustrate the musical creativity inspired by death and the social significance of song in fashioning responses to bereavement.

Musical conceptions of death

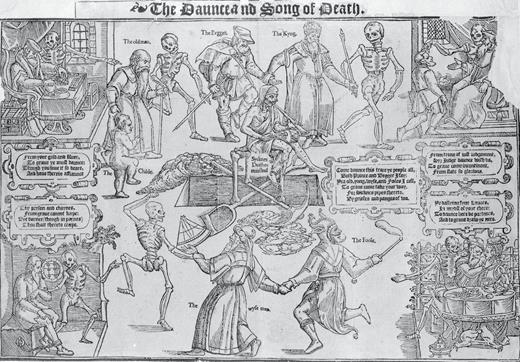

Formed from a mix of classical philosophy, mythology and religious belief, Elizabethan notions of death were surprisingly musical. One popular image was the ‘dance of death’. This depicted the universality of death, which comes to all whether rich or poor, young or old.16 Dating back to the late medieval period, the idea survived the Reformation in prints such as The Dance and Song of Death (1569) (illus.1). Death’s grotesque minstrel, Sickness, plays the pipe and tabor at the centre of a circle dance while skeletons lead the dancers. Circle dances were communal affairs in which people of all classes might participate.17 The power of music to draw people into the dance and its socially inclusive nature evoked the egalitarian and inescapable force of death.

The Dance and Song of Death (1569) (© The British Library Board, Huth.50.(32))

While the dance was metaphorical, there were also philosophical arguments for music’s association with dying. Physician John Case reported that people ‘growing faint in mind or near death’ claimed to hear music. Drawing on Boethian notions of a universal harmony that formed the heavens and the soul, Case interprets the phenomenon as the mind hearing the ‘heavenly music in the First Cause, whence it took its origin’.18 As the mind arose ‘from the First Cause and music’, it is ‘wonderfully captivated by music in its mortal journey’ and in death it is ‘perfected and blessed when returned to the First Cause and to Music’.19 Music links the soul to heaven, and death is a musical experience as earthly sounds fade and one begins to hear the celestial harmony. Such philosophical notions of heavenly music had a more popular counterpart in portrayals of heaven as filled with singing angels and saints. I. B.’s Looking Glass of Mortality (1599) drew on the imagery of the book of Revelation in describing heaven as a place where ‘evermore the Angels ... do sing’, while the harmony of the blessed Saints ‘In every street doth ring’ such that ‘God’s praises there are always sung / With harmony most sweet’.20

Finally, in bird lore, swans were said to sing just once: an exquisitely beautiful song, just before their deaths. Case described how the swan ‘as if desiring its demise, sings a little before its death, closing its unhappy life with voice and celestial harmony’.21 As in his story of near-death music, singing forms a liminal space between life and death, and between earth and heaven. In Thomas Blague’s School of Wise Conceits (1565), the swan-song was a moral exemplar for why death should be embraced rather than feared. The swan sings because it shall no longer be ‘troubled with seeking for meat’ nor ‘need to fear the Fowler’s gun’, so Blague concludes: ‘we are warned hereby not to fear death, being by that bereft from all miseries’.22 As in the philosophical notions of music and death, song characterizes the transitional state between life and death, simultaneously sounding a final despair of life and a foretaste of heavenly harmony.

Death songs and the stage

These legendary birdsongs have similarities with a type of stage song that arose in the 1560–70s, the aptly named ‘death songs’.23 Written for a solo voice whose interjections cut through the contrapuntal texture provided by a consort of viols, these were a subgenre of the songs performed by the choirboy acting companies of the Chapel Royal and St Paul’s Cathedral. Although the plays contained a variety of song styles, it was primarily the laments—a large proportion of which are death songs—that were preserved, probably because they were valued as the most affective and eloquent songs of the repertory. As the protagonist (typically female) expresses her grief and gives herself up to death, the songs present an outpouring of eloquence in the face of impending death that mirrors the mythological swan song.

Richard Farrant was Master of the Choristers at the Chapel Royal and St George’s Chapel, Windsor, and his Alas you Salt Sea Gods is one of the few songs whose play is extant.24 It appears to come from The Wars of Cyrus, which was probably first performed by the Chapel Royal choirboys in c.1576–80, though only printed in 1594.25 The play text contains no musical cues, but the song was most likely sung before Panthea commits suicide, following the death of her husband Abradad. The song is a rhetorical set-piece, combining several typical features:26 exclamations of ‘ah’ and ‘alas’; extensive alliteration in phrases like ‘send sobs, send sighs, send grievous groans’; and formal invocations to the ‘Salt Sea Gods’ to hear her lament and to ladies to accompany it. These rhetorical features are accompanied by similarly stylized musical figures, such as falling and sighing motifs for ‘alas’, ‘sobs’ and ‘sighs’, and repeated exclamations of rising pitch and increasing intensity.

Panthea’s plea to the gods to send sighs and groans and to strike her dead draws on the Elizabethan belief that grief could cause death.27 Like the swan whose song was interpreted as a sign of the welcomeness of death, to Panthea death will be ‘most sweet’, and she ends her song by declaring that she ‘craves to die’. Although she ends her life by stabbing herself, this is not condemned as suicide. Instead, Panthea’s maid declares her ‘Slain with self grief for Abradates’ sake’, and Cyrus vows to erect a grand monument in honour of her marital chastity and virtue.28 While Christianity condemned self-murder as a mortal sin, the lover-suicides of classical figures such as Pyramus and Thisbe and the medieval courtly love tradition offered a contrasting approach. So while in practice the law dealt with suicides with increasing severity in the 16th century, literary representations of such lover-suicides often offered a more sympathetic assessment, emphasizing the lovers’ reunion in heaven or the tragic dangers of extreme passions.29 Other death songs incorporate the death itself: in the anonymous Come tread the paths, the protagonist calls out to her slain lover, Guichardo, ‘I yield to thee my ghost’ and in the final lines she cries to the audience: ‘Ah, see! I die’.30

The rhetorical artifice of such scenes would only be enhanced by the heroine’s representation by a boy actor. The doll-like effect of children playing adult characters and the disparity of gender would be joined in this moment by the spectators’ awareness that this was a musical set-piece designed to showcase a choirboy’s talents.31 The ambivalent status of these child actors—disempowered by age yet earning admiration via their voices—paralleled these heroines, disempowered by fate, yet to some extent re-empowered by their eloquent song, as well as by taking their lives into their own hands. Moreover, the fashion for pathetic-heroine plays in the 1570–80s was probably intended to flatter the queen—a particular patron of these choirboy companies—indirectly by highlighting the strengths and virtues of her sex.32 The image of dying in these songs has little to do with the reality of death. Rather, this idealized death is the means through which Panthea is transformed from a mortal woman to a paradigm of marital chastity and virtue. As in the swan’s song, music defines the liminal space between life and death. Death is the moment when earthly and celestial music come closest, inspiring an eloquent musical farewell before the soul’s final liberation from its miseries to receive its heavenly rewards.

Songs for the deceased

Death songs were the direct forerunners of a new English fashion for sung elegies for the dead (to be distinguished from love elegies or more generalized grief) that developed from the 1580s onwards. Initially, these too were consort songs employing many of the same rhetorical devices. Later they spread into the madrigal collections and lute-songs of the 1590s.33 How did these songs represent death and fashion responses to bereavement?

Rituals of mourning and memorial were still emotionally and socially important, even if the Reformation had reduced the opportunities to achieve this through public worship. Mourners felt a responsibility to provide due ceremonies befitting the deceased’s status in life, to mourn but express hope in their resurrection, to commemorate their life, and to perpetuate their good name.34 As the majority of elegies survive in print and commemorate the deaths of socially important figures, sung elegies were one means for the upper classes to fulfil these public duties.

The eloquent expression of grief was believed to be therapeutic. Writer George Puttenham saw poets as acting like physicians, making ‘one short sorrowing the remedy of a long and grievous sorrow’.35 Poets and songwriters therefore did not necessarily express a personal loss, but might write on behalf of the bereaved. Insufficient information exists to judge accurately the relationship between the composer and the deceased in many cases, so it is not possible to distinguish between commissioned elegies and personal loss. Rather, these songs can be explored as artistic performances of socially acceptable responses to death and bereavement.

Funeral elegies were as variable in tone and purpose as they were in genre. Many were laments, but others presented joyful visions of the deceased in heaven. Elegies commemorated both Catholics and Protestants, as the impulse to memorialize and make moral examples of the virtuous was shared. Defining the religious outlook of any elegy is complicated when the beliefs of the deceased, composer or lyricist are not always clear, and when Catholic composers provided elegies for known Protestants. Nevertheless, some do commemorate prominent religious figures, and while there was much common rhetoric, some also contain identifiably Protestant themes.

After 20 years of relative stability, Reformation notions of death and the futility of intercessory singing were slowly becoming embedded in society by the 1580s (excepting the deliberate resistance of Catholics).36 One positive effect of the Reformation’s denial of purgatory was that friends and families might now envisage the deceased as immediately in heaven. Elegies could therefore be more cheerful than grief-stricken, drawing on popular images of a musical heaven to depict consoling images of the deceased’s celestial joys. Thomas Morley’s elegy for Henry Noel (d.1597)—possibly the musical courtier figured in the ‘Bonny-boots’ madrigals37—imagines his earthly talents transformed to heavenly purposes:

Hark! Alleluia cheerly

With Angels now he singeth

That here loved music dearly.38

The heavenly joys are perhaps somewhat muted by Morley’s departure from the light, Italianate style of the other canzonets of the volume, to a more austere, imitative polyphony in measured minims.39 Yet Noel’s continued musicality portrays death as not his end, but merely his displacement from earthly society to the community of heaven. In contrast to the radical separation of the dead and the living in Reformation theology—neither were believed capable of influencing the other’s condition40—here music offers a consolatory link between the earthly and heavenly realms. In the act of singing, the living singers mirror Noel’s participation in the heavenly choirs, their earthly alleluias imitating the divine.

Yet images of heavenly music-making can be found in elegies for Catholics too, as those of exceptional piety might still be believed to have passed straight into heaven. This is the case in Why do I use my paper, ink and pen?, Henry Walpole’s elegy for Jesuit martyr Edmund Campion (the first verse was set by William Byrd, along with two new ones). Contrasting his earthly suffering and heavenly joys, Walpole imagined that:

for men’s reproach with angels he [Campion] doth sing a sacred song which everlasting is.41

Elegies for Catholics and Protestants might share musical imagery, if not their theology.

The musical expression of grief

With the deceased now believed to be enjoying immediate heavenly bliss, considerable anxiety arose for some Protestants concerning the appropriateness of grief. In the mid- to late 16th century grief was viewed as revealing irrationality, weakness, inadequate self-control and impiety. At the extreme, some writers denied the appropriateness of any mourning for those who had died virtuously and were therefore in heaven.42 In elegies, the futility of lament was frequently represented through a contrast between joyful music and weeping or mourning. Thomas Watson’s elegy for Sir Philip Sidney, How long with vain complaining, argues:

Sweet Sidney lives in heav’n, O therefore let our weeping,

Be turn’d to hymns and songs of pleasant greeting.43

Watson’s lyrics are a contrafactum on Luca Marenzio’s Questa de verd’ herbette in Italian Madrigals Englished (1590). Nevertheless, Watson skilfully matches his juxtapositions of sorrow and heavenly joy to Marenzio’s musical contrasts between slower-paced, homophonic passages versus livelier imitative or triple-time sections. A shift from the prevailing cantus mollis (with By) into cantus durus (with B}) becomes a vision of eternal gladness, while rising scales are paired with Sidney’s ascent to heaven. As this elegy was published in 1590 in a volume dedicated to the Earl of Essex, who had recently married Sidney’s widow, its cheery tone may also reflect the end of the mourning period and a shift towards fond remembrance.44

Although calling for moderation in mourning was more common than total denial, such views were often still severe in their expectations of self-control and a swift return to normality.45 In For death of her—an elegy for one Mary Gascoigne (d.1588) by the Norwich composer William Cobbold—the lyrics express the belief that Mary’s virtues must have ensured her place in heaven. The appropriateness of the protagonist’s grief is therefore uncertain and he confesses:

I know not well (though it lies in my choice)

Whether I should lament or else rejoice.46

Yet he is aware that the choice is his alone, bearing no effect on Mary’s destiny.

In seeking to display moderate grief, many elegies have striking reversals of tone as they seek to temper their mourning with faith in the deceased’s entry into heaven. William Byrd’s elegy for Sir Philip Sidney, Come to me grief for ever, begins as a heartfelt lament. While the singer presents his grief as ‘helpless’, he also believes it to be ‘just grief’ and ‘plaint worthy’.47 His grief is focused on his loss and the extinguishing of an individual who graced court and country, and brought happiness to his friends: ‘Sidney is dead, O dead’, he repeats. A few verses later, however, the sentiment is suddenly reversed as the singer remembers both the Christian promise of eternal life and secular, classical notions of immortal fame:

Dead? No, but renowned

With the anointed one,

Honour on earth at his feet,

Bliss everlasting his seat.

In this instance the comfort is fleeting. Byrd’s setting is strophic, so no new musical mood supports the poetic change, while the song ends by repeating the opening verse, making grief the enduring emotion.

In the final decades of the 16th century, approaches to mourning were beginning to change. Attitudes towards grief were increasingly sympathetic and anxiety over expressing emotions was reducing. Grieving was recognized as a natural response to bereavement, and insufficient mourning could now be seen as a lack of humanity. In poetry, hyperbolic expressions of grief with no concern over a lack of moderation were becoming more common.48 Sung elegies too began to express grief more freely and exaggeratedly, often presenting music as a vehicle for the outpouring of lament. In Weelkes’s Noel, adieu thou court’s delight, musical notes are imagined as able to cry as he commands them, ‘Bedew my notes, his death-bed with your tears’.49 Grief in this elegy is far from moderate, and it ends on a disconsolate note: ‘Time helps some grief, No time your griefs out wears’. Francis Pilkington’s elegy for Thomas Leighton (d.1600), Come all you that draw heaven’s purest breath, even portrays music as uniquely able to express lament. Since both words (plaints and laments) and mere sounds (tears, groans, cries and sighs) have proved insufficient, the singer turns to ‘accents grave, and saddest tones’ in order to ‘Offer up Music’s doleful sacrifice’.50 The idea of sacrifice evokes the sense of duty still felt towards the dead to mourn and memorialize them, if no longer to pray for them.51

Music and memory

The majority of elegies survive because they were published in printed collections, so they are public acts of lament or commemoration more than expressions of private grief.52 The formal rhetoric can be seen in frequent invocations to Muses or angels (in parallel with the earlier death songs) to join this eloquent mourning. Pilkington’s lute-song for Leighton begins

Come all you that draw heaven’s purest breath,

Come Angel breasted sons of harmony.

Let us condole in tragic Elegy.53

These songs are comparable to published funeral sermons, or the erection of funeral monuments. Many epitaphs expressed the need for a lasting memory of the deceased. Whereas prior to Reformation this sentiment had been associated with continued intercession, now this perpetuating of fame was regarded as the just deserts of a virtuous life. A personal desire to remember combined with a more secular, humanist concern for the importance of individual fame.54 For example, Thomas Weelkes’s elegy for Lord Thomas Borough (d.1597), Cease now delight, declares:

Borough is dead, great Lord, of greater fame,

Live still on earth, by virtue of thy name.55

Memory and fame were forms of eternal life, through the survival of name and reputation. Eloquent music could be a fitting memorial, as Pilkington’s elegy made explicit:

Let these accords which notes distinguish’d frame, Serve for memorial to sweet Leighton’s name.56

Despite the transience of music in performance, the printing of these elegies provided a permanent record, while through repeated singing the listeners and performers would recall the deceased and perpetuate their memory.

Although praying for the dead continued in Catholic circles, musical memorials were still important there also, particularly as some of those they sought to remember had tarnished reputations in wider society. Few of Byrd’s elegies for Catholics were published (the elegy for Campion being an exceptional case); however, if they did not function so much as public memorials, they were musical monuments for a specific community, reinforcing their sense of identity through the remembrance of key Catholic figureheads. Byrd’s elegy for Mary Tudor was written not immediately after her death but post-1606, when James I had denied her a monument to match that of Elizabeth I.57 Instead, the lyrics of Crowned with flowers imagine the Muses constructing Mary’s memorial in heaven. Similarly, Byrd’s In angel’s weeds vindicates Mary Queen of Scots by imagining her now as a heavenly angel, before using her life as a moral for the frailty of earthly delights and fickleness of fortune.58

Memorials were frequently justified by their usefulness to the living. Funeral monuments became objects of contemplation for the devout, with people visiting churches specifically to view the tombs. They continued the function of the medieval memento mori in reminding the beholder of the inevitability of death, while offering exemplars of virtuous lives for emulation.59 Funeral sermons were similarly justified as praising God for the deceased and instructing the living.60 Songs could serve similar purposes and Byrd’s O that most rare breast opens with an assessment of Sir Philip Sidney’s virtues:

O that most rare breast, crystalline sincere,

Through which like gold thy princely heart did shine,

O sprite heroic, O valiant worthy knight,

O Sidney, prince of fame and men’s good will.61

The description of Sidney’s pure heart, heroism and popularity preserves his reputation for posterity and highlights the qualities other young men should imitate. The notion of mourning as a duty to the deceased also returns as the more grief-laden ending pays the ‘doleful debt due to thy hearse’. Byrd’s elegy for Lady Magdalen Browne, Viscountess Montague, who had established a Mass centre and shelter for Catholic priests at Battle Abbey, similarly makes her a virtuous paradigm. With lilies white extols her virtues as one who ‘wed themselves to our great Lord and Saviour’ and ‘solely lived in chaste and sweet behaviour’.62

Death, discord and silence

The songs so far have suggested a positive relationship between music, death, memorial, grief and consolation; however, music also provided imagery that emphasized the finality of death as destruction of life and nature. In Byrd’s Ye sacred Muses, a consort song lament for Thomas Tallis (d.1585), death not only kills the person, but also silences his creativity: ‘Tallis is dead and music dies’.63 Indeed, Tallis had such stature that all music is said to have perished with him. While hyperbolic, one of the social functions of laments was to acknowledge the gap left in society by the deceased.64 The lyrics captured Tallis’s importance in musical society and the significance of his loss. While Byrd’s close working relationship with Tallis makes this grief personal, the tone is nevertheless formal, from the opening invocation of the Muses to the final phrase’s slightly ironic (though formally typical) repetitions of ‘music dies’. While these repetitions seemingly belie music’s death, the unusual extended melisma on ‘music’ in the final phrase evokes again the notion of the exquisite swan song. The association is particularly apt, as the musical hero Orpheus was turned into a swan upon his death.

William Holborne employed the same trope of death as silencing in the contrasting style of a canzonet, SinceBonny-boots was dead (possibly for Henry Noel).65 After praising him as one who ‘so divinely / Could toot and foot it’, the light-hearted pastoral mood takes a melancholic turn as his fellow shepherds ‘ne’er went more a-Maying / Nor heard that sweet fa-la-ing’.66 As dancing to the pipe and singing were communal and participatory forms of musical recreation, the silencing signifies not only a creative loss—the literal effect of death on the melodies of the deceased musician—but also a social one. The merry band of shepherds is dispersed by the death of its ringleader.

Other elegies use the image of discord to emphasize the social and emotional disorder brought by bereavement, and represent death as a deforming of the natural order. In Richard Carlton’s madrigal, Sound saddest notes, the impact of Sir John Shelton’s death is a distorted harmony as grief infiltrates the music:

Tune every strain with tears and weeping,

Conclude each close, with sighs and groaning.67

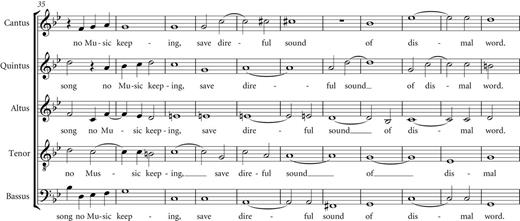

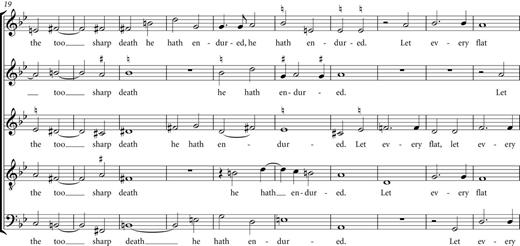

Although sung, it is no longer music but ‘direful sound’. Employing typical madrigalian word-painting, Carlton illustrates this ‘direful sound’ with an unexpected chromatic moment in the cantus part (ex.1) that jerks the harmony from a minor chord on A to a major one (even more striking as the phrase began a bar earlier with a major chord on C).

Richard Carlton’s ‘direful sound’ in Sound saddest notes, bars 35–45, from Madrigals to five voices (London, 1601), sig.c4v–d1r

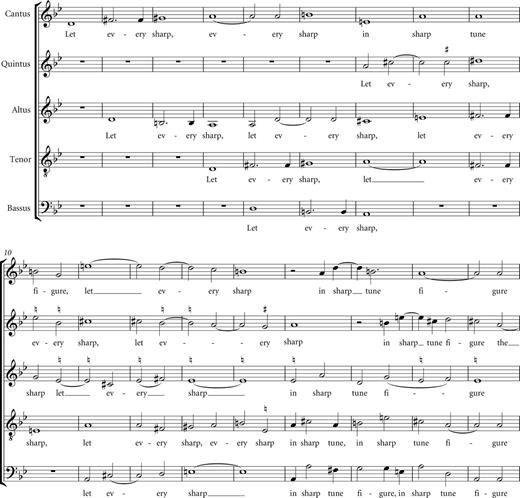

Grief emerges as merely a symptom of the greater discord that is death itself. In the second verse, music depicts the ‘too sharp death’ Shelton endured. Carlton took this obvious opportunity for word-painting to extremes. Over a passage of 25 semibreves Carlton sharpened every note in the scale during the lines ‘Let every sharp, in sharp tune figure / the too sharp death he hath endured’. From a signature of two flats the harmony is wrenched into deploying (initially) three sharps, cadencing on A (ex.2, bar 4). This sharpwards trend continues with a cadence on E (bar 10) and an unexpected shift onto a major chord on B at ‘too sharp’ (bar 19). If a cadence is made into bar 21, the resulting A! means that every note of the original two-flat scale has been sharpened.68 The extreme accidentals and surprising shifts of harmony create a music that is strange and distorted, an exaggerated example of the sharpwards shift for ‘direful sound’. The performers and listeners were transported into unfamiliar tonal territory evoking the greater unknowns of the domain of death. The call to ‘let every flat, show flat the rigour / of Fortune’s spite’ results in an abrupt return to the mode—flattening all the proceeding sharps—and to the world of the living where all are subject to Fortune.

Richard Carlton’s depiction of the sharpness of death in Sound saddest notes, part 2, bars 1–28

Conclusion

Though the Reformation influenced both the increasing prevalence of elegies and some of the responses to death within them, this was by no means a Protestant genre. Remembrance was crucial to Catholics’ sense of continued connection with their dead, the celebration of their martyrs and their sense of communal identity, so they too participated in the trend for musical elegies. The shared tendency towards moralizing and memorializing in these elegies is a reminder that despite the theological differences, responses to death by Catholics and Protestants could still share many features, particularly within more secular genres. In Elizabethan England music provided the means, the imagery and the cultural associations to serve in the staging of death, the representation of loss and disorder, and acts of consolation or remembrance for people across the religious spectrum. Music’s position as earthly pleasure, soul’s harmony and divine concord gave it close associations with death and heaven that extended beyond liturgical devotions. Moreover, Elizabethan elegies expressed confidence in music’s ability to express grief and death even when words or weeping failed.

In the 17th century, the sung elegy would reach new heights in its outpourings of grief with the creation of whole collections of mourning songs, such as John Coperario’s Funeral Tears for the Death of the Right Honourable the Earl of Devonshire (1606) and Songs of Mourning Bewailing the Untimely Death of Prince Henry (1613). Significantly, these were collections of lute-songs, whereas few elegies of this genre were published in the Elizabethan period, despite the genre’s connections with melancholy. In the 16th century, the genre’s introspective qualities perhaps made it less suitable for the public, commemorative functions that elegies served, while its associations with melancholic excess may have raised concerns about immoderate grieving.

The Jacobean lute-song elegies marked a significant shift in musical responses to grief. In Elizabethan songs grief was usually communal and shared. The protagonists called on people and gods to join the laments, showed awareness of other mourners and were frequently aware of their role in memorializing as much as grieving. The lute-songs, however, were a performance of personal, individualized and incommunicable grief. According to Daniel Fischlin, their central strategy was the ‘inexpressibility topos’: the conceit that true grief was an experience too personalized and profound to be expressed by music or word, while death was literally inexpressible as it remained unknown and inexperienced by the living. Paradoxically, lute-songs represented the profundity of grief and death by staging their inability to contend with such mysteries.69 In the 17th century, death would no longer be the inspiration for musical eloquence, but rather its point of representational failure.

Thanks are due to the British Academy for the Humanities and Social Sciences for funding this research. Early modern spelling and punctuation have been modernized throughout.

The Praise of Music (Oxford, 1586), p.86.

D. Cressy, Birth, marriage, and death: ritual, religion, and the life-cycle in Tudor and Stuart England (Oxford, 1997), pp.386–7, 396–8; E. Duffy, The stripping of the altars: traditional religion in England c.1400–c.1580 (New Haven, 2005), pp.309–76, 474–5; P. Marshall, Beliefs and the dead in Reformation England (Oxford, 2002), pp.125–231; C. Gittings, Death, burial and the individual in early modern England (London, 1988), pp.39–44.

J. Bossy, The English Catholic community, 1570–1850 (London, 1975), pp.121–31, 140–1; J. Kerman, The Masses and motets of William Byrd (London, 1981), pp.49–51; K. McCarthy, Liturgy and contemplation in Byrd’s Gradualia (New York, 2007), pp.13, 100.

Duffy, Stripping of the altars, pp.571, 577–8; Cressy, Birth, marriage, and death, pp.398–402.

J. Harper, The forms and orders of Western liturgy from the tenth to the eighteenth century: a historical introduction and guide for students and musicians (Oxford, 1991), pp.181–2.

R. C. McCoy, Alterations of state: sacred kingship in the English Reformation (New York, 2002), pp.63–5; Marshall, Beliefs and the dead, p.181.

Kerman, Masses and motets, pp.31–5, 65–6; R. Charteris, Alfonso Ferrabosco the Elder (1543–1588), a thematic catalogue of his music with a biographical calendar (New York, 1984), pp.69, 76–7, 85–6.

J. Smith, ‘“Unlawful song”: Byrd, the Babington plot and the Paget choir’, Early Music, xxxviii/4 (2010), pp.497–508, at pp.500–2; K. McCarthy, Byrd (Oxford, 2013), pp.69–70.

J. Milsom, ‘Sacred songs in the chamber’, in English choral practice, 1400–1650, ed. J. Morehen (Cambridge, 1995), pp.161–79.

Other Byrd motets related to the Office for the Dead include Libera me Domine et pone me from Job xvii and Cunctus diebus from Job xiv, both of which are Matins lessons; Circumdederunt me dolores on part of Psalm 114 and Ad dominum cum tribularer from Psalm 119, both from Vespers; not to mention settings of several penitential psalms, which figured prominently in Catholic funeral services.

R. A. Houlbrooke, Death, religion, and the family in England, 1480–1750 (Oxford, 1998), pp.228, 254; M. Greenfield, ‘The cultural functions of Renaissance elegy’, English Literary Renaissance, xxviii (1998), pp.75–94, at p.84.

P. Le Huray, Music and the Reformation in England 1549–1660 (Cambridge, 1978), pp.248, 173; Houlbrooke, Death, religion, and the family, p.267; D. Poulton, John Dowland (London, 1982), pp.330–6.

Marshall, Beliefs and the dead, pp.265–308; V. Duckles, ‘The English musical elegy of the late Renaissance’, in Aspects of medieval and Renaissance music: a birthday offering to Gustave Reese, ed. J. LaRue (Oxford, 1967), pp.134–53.

W. Elders, Symbolic scores: studies in the music of the Renaissance (Leiden, 1994), pp.126–46; M. Boyd, ‘Elegy’, in Grove Music Onlinewww.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/08701; D. Moroney, ‘Déploration’, in Grove Music Onlinewww.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/07582 (accessed 28 November 2014).

Songs in which death is merely a metaphor for sexual love are omitted.

K. Meyer-Baer, Music of the spheres and the dance of death: studies in musical iconology (Princeton, 1970), pp.298–312, 321–5.

C. Marsh, Music and society in early modern England (Cambridge, 2010), pp.334–7.

John Case, Apologia musices tam vocalis quam instrumentalis et mixtae (1588), p.3. All translations are by D. F. Sutton, www.philological.bham.ac.uk/music (accessed 28 November 2014); Boethius, Fundamentals of music, trans. C. Bower, ed. C. Palisca (New Haven, 1989), pp.9–10. The ‘First Cause’ is a philosophical notion (drawn from Plato’s Phaedo) that if all causes are traced back to their origin one comes to the First Cause, often synonymous with God.

Case, Apologia musices, p.3.

I. B., A Looking Glass of Mortality (London, 1599), pp.47–8.

Case, Apologia musices, p.36.

Thomas Blague, A School of Wise Conceits (London, 1569), pp.80–1.

Consort songs, ed. P. Brett, Musica Britannica, xxii (London, 1974), p.xvi; G. E. P. Arkwright, ‘Elizabethan choirboy plays and their music’, Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, xl (1913), pp.117–38; P. Brett, ‘The English consort song, 1570–1625’, Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, lxxxviii (1961), pp.73–88, at pp.78–80.

Consort songs, ed. Brett, pp.15–17, 178; P. Le Huray and J. Morehen, ‘Farrant, Richard’, Grove music onlinewww.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/09332 (accessed 28 November 2014).

Richard Farrant, The wars of Cyrus: an early classical narrative drama of the child actors, ed. J. P. Brawner (Urbana, 1942), pp.10–20.

Brett, ‘English consort song’, p.79.

Cressy, Birth, marriage, and death, p.393.

Farrant, Wars of Cyrus, p.123.

M. McDonald and T. R. Murphy, Sleepless souls: suicide in early modern England (Oxford, 1990), pp.99–106.

Consort songs, ed. Brett, pp.3–5.

J. H. McCarthy, ‘Elizabeth I’s “picture in little”: boy company representations of a queen’s authority’, Studies in Philology, c (2003), pp.425–62, at pp.439–44, 454–5.

McCarthy, ‘Elizabeth I’s “picture in little”’, p.451.

Duckles, ‘English musical elegy’, pp.134–53, which includes a list of late 16th- and early 17th-century English elegies for the deceased.

Marshall, Beliefs and the dead, p.265.

George Puttenham, The art of English poesie (London, 1589), p.39.

Duffy, Stripping of the altars, p.586.

D. Greer, ‘“Thou court’s delight”: biographical notes on Henry Noel’, Lute Society Journal, xvii (1975), pp.49–59.

Thomas Morley, Canzonets or little short ayres to five and six voices (London, 1597), sig.f1r.

Duckles, ‘English musical elegy’, pp.141–2.

Duffy, Stripping of the altars, p.474; Marshall, Beliefs and the dead, pp.210–31.

Thomas Alfield, A true report of the death and martyrdom of M. Campion Jesuit and priest ... at Tybourne the first of December 1581 (London, 1582), sig.e4v; William Byrd, Psalmes, Sonets and Songs (1588), ed. J. Smith, The Byrd Edition, xii (London, 2004), pp.xxxix, 150–4.

Houlbrooke, Death, religion, and the family, pp.221–3; G. W. Pigman, Grief and English Renaissance elegy (Cambridge, 1985), pp.2–3, 27–9.

Thomas Watson, Italian madrigals Englished: 1590, ed. A. Chatterley, Musica Britannica, lxxiv (London, 1999), pp.66–9.

William Byrd, Psalms, sonnets and songs of sadness and piety (London, 1588), sig.g1r. See also K. Duncan-Jones, ‘“Melancholie times”: musical recollections of Sidney by William Byrd and Thomas Watson’, in The well-enchanting skill: music, poetry, and drama in the culture of the Renaissance: essays in honour of F. W. Sternfeld, ed. J. Caldwell, E. Olleson and S. Wollenberg (Oxford, 1990), pp.171–80, at p.178.

Pigman, Grief and English Renaissance elegy, p.39.

Consort songs, ed. Brett, pp. 25–6.

Byrd, Psalms, sonnets and songs, sig.g1r. See also Duncan-Jones, ‘“Melancholie times”’, pp.176–7.

Cressy, Birth, marriage, and death, p.393; Pigman, Grief and English Renaissance elegy, pp.2–3, 39, 52–67.

Thomas Weelkes, Madrigals of 5 and 6 parts (London, 1600), sig.d3v–d4r.

Francis Pilkington, First book of songs or ayres of 4 parts (London, 1605), sig.m1v–m2r.

Marshall, Beliefs and the dead, p.265.

Byrd’s elegies for Catholics are the exception here, as shown below.

Pilkington, First book, sig.m1v–m2r.

Marshall, Beliefs and the dead, pp.269–73; Houlbrooke, Death, religion, and the family, p.352.

Thomas Weelkes, Ballets and madrigals to five voices (London, 1598), sig.d4v.

Pilkington, First book, sig.m1v–m2r.

J. Kerman, ‘The Elizabethan motet: a study of texts for music’, Studies in the Renaissance, ix (1962), pp.273–308, at p.297; P. Taylor, ‘Memorializing Mary Tudor: William Byrd and Edward Paston’s “Crowned with flowers and lilies”’, Music & Letters, xciii (2012), pp.170–90; P. Taylor, ‘“O worthy queen”—Byrd’s elegy for Mary I’, The Viol, v (2006–7), pp.20–4; William Byrd, Consort songs for voice and viols, ed. P. Brett, The Byrd Edition, xv (London, 1970), pp.100–6.

Byrd, Consort songs, pp.111–18.

N. Llewellyn, Funeral monuments in Post-Reformation England (Cambridge, 2000), pp.337–53.

Marshall, Beliefs and the dead, pp.277–8.

Byrd, Psalms, sonnets and songs, sig.g1v–g2r. See also K. Duncan-Jones, ‘“Melancholie times”’, pp.176–7.

Byrd, Consort songs, pp.149–51; P. Taylor, ‘Elegiac consort songs in the Paston music collection’, The Viol, xxiv (2011), pp.7–9.

Byrd, Consort songs, pp.114–18. For an analysis, see M. Smith, ‘“Whom music’s lore delighteth”: words-and-music in Byrd’s Ye sacred Muses’, Early Music, xxxi/3 (2003), pp.425–36.

Greenfield, ‘Cultural functions’, pp.81–2.

Greer, ‘“Thou court’s delight”’, pp.49–59.

William Holborne, ‘Since Bonny-boots was dead’, The cittern school (London, 1597), sig.q2v–q3r.

Richard Carlton, Madrigals to five voices (London, 1601), sig.c4v–d1r.

Such a cadence would seem natural to the quintus part, though not necessarily to the tenor, which also sings an A. An alternative interpretation would be that when sight-singing, the quintus singer (anticipating a cadence) might be misled into singing ‘too sharp’ against the tenor.

D. Fischlin, ‘“Sighes and tears make life to last”: the purgation of grief and death through trope in the English ayre’, Criticism, xxxviii (1996), pp.1–25.