-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Richard G. King, ‘How to be an emperor’: acting Alexander the Great in opera seria, Early Music, Volume 36, Issue 2, May 2008, Pages 181–202, https://doi.org/10.1093/em/cam136

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Employing the example of Alexander the Great in opera seria, this essay reconsiders the performance of heroic roles in the 18th century. One of its aims is to extend our current understanding of Baroque gesture by taking seriously what contemporary acting tutors and treatises say: a complete performance is possible only after careful study of gesture in painting and statuary. An examination of Alexander iconography suggests both specific tactics for the singer, director and designer; and, more importantly, a broader agenda: the representation of Alexander's essential grandeur. A second goal is to determine to what extent our performances today of Alexander and other operatic heroes can be shaped by comprehension of their significance and meanings for those who created and consumed heroic art in the 18th century. These heroes were (and are) not interchangeable, not simply emblems, but rather, individuals whose stories conjured up a host of resonances specific to each. We might portray them accordingly. Finally, the article explores some of the aesthetic and philosophical questions raised by this kind of historical approach.

THE inspiration for this essay is a remark by Reinhard Strohm that sounds contentious at first, but upon reflection acquires flavour and depth. Concerning the performance of opera seria, Strohm once observed:1

Here is much food for thought: the ‘work’ concept in the Baroque era, historical staging and its value, the performer’s role and so forth. What I find provocative is Strohm’s suggestion that if we had a performer who understood singing, declamation and ‘how to be an Emperor’, it would matter little what music that singer actually performed. This essay contemplates the last of these requirements, exploring what it meant to be an emperor on stage in Handel’s and Hasse’s times by studying the example of Alexander the Great in opera seria. One of my aims is to extend our current understanding of Baroque gesture by taking seriously what contemporary acting tutors and treatises say: a complete performance is possible only after careful study of gesture in painting and statuary. A second goal is to determine to what extent our performances today of Alexander, and by extension other operatic heroes, can be shaped by comprehension of what it means ‘to be an Alexander’. Finally, I consider some of the aesthetic and philosophical questions that such an historical approach raises.What was clearly fixed and predetermined about any production in those days had so little to do with the score and so much to do with the presentation of the drama by a single, individual singer that a revival of opera seria today should really concentrate less on what Handel or Hasse wrote than on what Senesino or Farinelli did with the chief role. The mere reconstruction of the stage settings, costumes etc. (probably without the corresponding stage-technique) has no historical value. But if we had a Senesino, who had a deep understanding not only of singing but also of reciting Italian verse and not least of how to be an Emperor it might not matter so much that some of his arias were by Harnoncourt and not Handel. In fact they could even be by Penderecki: a conclusion that is only apparently absurd, since the claims of history in the matter of musical performance always collapse in cases where the performer has to become the creator.

Despite the fact that acting, like singing, is an ephemeral art,2 the basic principles of 17th- and 18th-century stage gesture are well known, thanks in large part to the work of Dene Barnett.3 These principles are likely to be familiar to readers of this journal; nevertheless, a brief summary may prove useful for what is to follow.

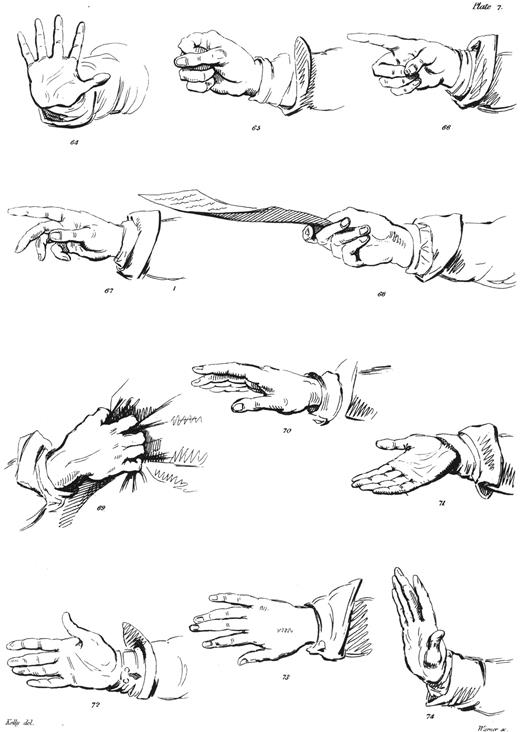

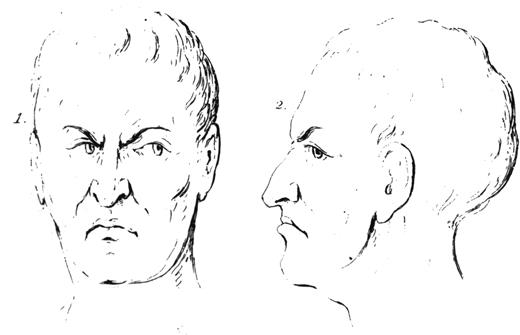

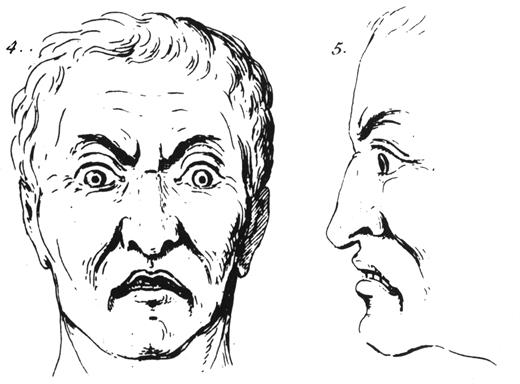

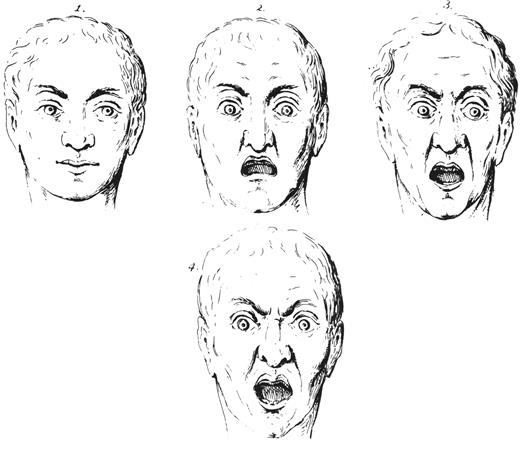

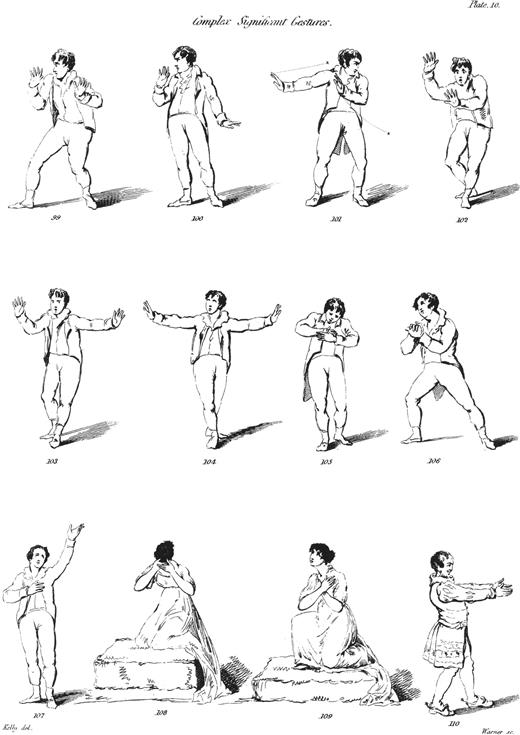

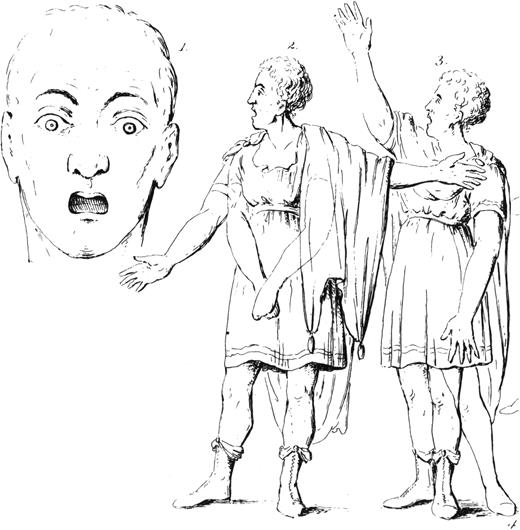

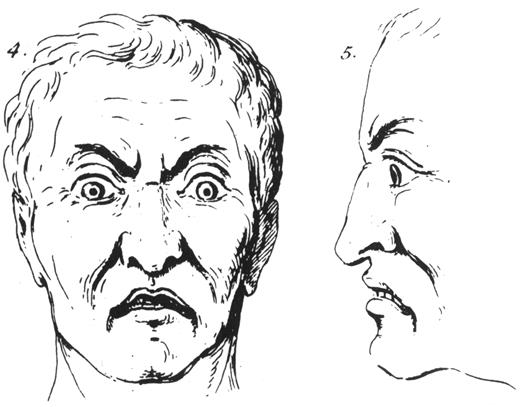

An important function of gesture was to create for the spectator a concrete image of the ideas or affects expressed by the words and music. The emphasis was on the hands (illus.1) and face (illus.2a-e)—these were the main vehicles used to express affect. Gesture preceded speech, as a kind of preparation, and each gesture generally began with the eyes, followed, in order, by the face, head, hands and arms, feet and, finally, voice; the audience often saw the affect before the text expressing it was sung or spoken (illus.3).4

‘Positions and motions of the hands’ (Gilbert Austin, Chironomia; or a Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery … (London: printed for T. Cadell and W. Davies, by W. Bulmer, 1806), pl.7)

Facial gestures (Johannes Jelgerhuis, Theoretische lessen over de gesticulatie en mimiek … (Amsterdam: Warnars, 1827)) (a) contempt (pl.38); (b) fright (pl.34); (c) grief and weeping (pl.45); (d) anger (pl.32); (e) from tranquillity to surprise to amazement to horror (pl.33)

‘Complex significant gestures’ (Gilbert Austin, Chironomia, pl.10): aversion, horror (99); successive gestures to express aversion (100–101); horror (102); listening (fear) (103); admiration (104); veneration (105); deprecation (106); appealing to heaven (107); shame (108); mild resignation (109); surprise and welcoming (110)

The positioning of characters on stage was just as rigorously prescribed; for example, when more than a few actors or singers were on stage, they would be arranged in a semicircle. The semicircle clarified social rank: the most important person was placed upstage and centre, the rest were gathered around to the right and left in order of their social and dramatic importance.5 A character's role and even nature thus could be shown by his or her position on stage.

This formal, highly codified acting technique made the singer's job easier. Once learned, the gestures could be used again and again. The performer would have ‘acted’ them all before, often to the same text (for example, in settings of Metastasio's librettos), or even to the same text and music (in the case of baggage arias).

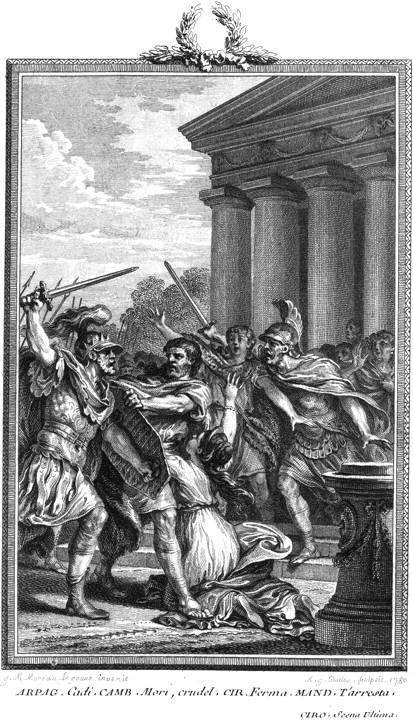

Acting must have involved a process of boiling the text and music down to their essential affects, and devising appropriate gestures for each. To illustrate both this process and the general principles outlined above, I provide an example from Handel's 1726 opera Alessandro (see Table 1). The scene is the Temple of Jupiter, where all have gathered to pay tribute to Alessandro (Alexander the Great). Following a French overture, Alessandro addresses Jupiter, whom he considers to be his father, and then receives tribute from Tassile and flattery from Cleone, who prostrates himself before the conqueror. Clito, outraged by Cleone's action, refuses to do the same. Alessandro is surprised, and then angry: he throws Clito to the ground and forces him to prostrate; vowing revenge, Clito exits. The images labelled a-i in illus.4 and the first column of Table 1, drawn from a variety of sources, are suggestions for gestures to match the very basic ‘affective analysis’ provided in the second column of the Table.

Paolo Antonio Rolli, Alessandro (London, 1726), Act 1, scene 9

| a | REVERENCE/AWE | Alessandro: Primo motor delle Superne Sfere Da te nato Alessandro umil t’adora Come lor pregio che da te deriva Rendono gli altri Dei; Egli ti rende ancora Tutto l’illustre Onor de’suoi Trofei. | Alexander: Thee, first great Mover of Supernal Spheres, Thy Son, thy Alexander humbly worships; As other Gods, whom all Mankind reveres, Offer the Glories they derive from thee, He pays the Trophies of his Victory. |

| b | ADULATION | Tassile: Figlio del Re degl’immortali Numi, A Giove e a Te porto dell’India i Voti. | Taxiles: Son to the King of the immortal Gods, To Jove and thee I bring all India’s Pray’rs. |

| c | PROSTRATION | Cleone: Nato di Giove, sovruman Monarca, Invitto, Augusto, Pio, Sommo, Divino, Con l’Universo a Giove m’inchino. | Cleon: O, born of Jove, chief Monarch of the Earth, Pious, August, Invincible, Divine, To Jove and thee, thus, bowing Worlds incline. |

| d | AVERSION | Clito: (Fremo di rabbia) Io, sol m’inchino a Giove. Tu per sangue e Valor, Re nostro sei. Ti basti ciò: non insultar gli Dei. | Cleitus: (I burn with Rage) I bow alone to Jove: Thou art our King in Valour, and by Blood; Let that suffice thee; nor insult the Gods. |

| e | SURPRISE | Alessandro: Empio, a i Numi negar tenti il rispetto? | Alexander: Would'st, impious, shun Respect to Gods to pay? |

| f | ANGER | Cadi, prostrati, adora a tuo dispetto. | Fall, prostrate, worship, and by Force obey. |

| g | [Clito’s FEAR] | ||

| h | VIOLENT GESTURETERROR | [Lo prostra a forza.] | [He lays him prostrate by force.] |

| i | TERROR | Clito: E ad un’antico tuo Fedel, tal fai Violenza ed inguria? Aless: Empio, superbo, Va altrove ad infuriar. Clito: Ti pentirai. [Parte.] | Cleitus: To one grown old in Loyalty, do you Offer such Violence and such Injustice? Alexander: Thou haughty, impious Wretch; go, rage elsewhere. Cleitus: Most certain you’ll repent it. [Exit.] |

| a | REVERENCE/AWE | Alessandro: Primo motor delle Superne Sfere Da te nato Alessandro umil t’adora Come lor pregio che da te deriva Rendono gli altri Dei; Egli ti rende ancora Tutto l’illustre Onor de’suoi Trofei. | Alexander: Thee, first great Mover of Supernal Spheres, Thy Son, thy Alexander humbly worships; As other Gods, whom all Mankind reveres, Offer the Glories they derive from thee, He pays the Trophies of his Victory. |

| b | ADULATION | Tassile: Figlio del Re degl’immortali Numi, A Giove e a Te porto dell’India i Voti. | Taxiles: Son to the King of the immortal Gods, To Jove and thee I bring all India’s Pray’rs. |

| c | PROSTRATION | Cleone: Nato di Giove, sovruman Monarca, Invitto, Augusto, Pio, Sommo, Divino, Con l’Universo a Giove m’inchino. | Cleon: O, born of Jove, chief Monarch of the Earth, Pious, August, Invincible, Divine, To Jove and thee, thus, bowing Worlds incline. |

| d | AVERSION | Clito: (Fremo di rabbia) Io, sol m’inchino a Giove. Tu per sangue e Valor, Re nostro sei. Ti basti ciò: non insultar gli Dei. | Cleitus: (I burn with Rage) I bow alone to Jove: Thou art our King in Valour, and by Blood; Let that suffice thee; nor insult the Gods. |

| e | SURPRISE | Alessandro: Empio, a i Numi negar tenti il rispetto? | Alexander: Would'st, impious, shun Respect to Gods to pay? |

| f | ANGER | Cadi, prostrati, adora a tuo dispetto. | Fall, prostrate, worship, and by Force obey. |

| g | [Clito’s FEAR] | ||

| h | VIOLENT GESTURETERROR | [Lo prostra a forza.] | [He lays him prostrate by force.] |

| i | TERROR | Clito: E ad un’antico tuo Fedel, tal fai Violenza ed inguria? Aless: Empio, superbo, Va altrove ad infuriar. Clito: Ti pentirai. [Parte.] | Cleitus: To one grown old in Loyalty, do you Offer such Violence and such Injustice? Alexander: Thou haughty, impious Wretch; go, rage elsewhere. Cleitus: Most certain you’ll repent it. [Exit.] |

Paolo Antonio Rolli, Alessandro (London, 1726), Act 1, scene 9

| a | REVERENCE/AWE | Alessandro: Primo motor delle Superne Sfere Da te nato Alessandro umil t’adora Come lor pregio che da te deriva Rendono gli altri Dei; Egli ti rende ancora Tutto l’illustre Onor de’suoi Trofei. | Alexander: Thee, first great Mover of Supernal Spheres, Thy Son, thy Alexander humbly worships; As other Gods, whom all Mankind reveres, Offer the Glories they derive from thee, He pays the Trophies of his Victory. |

| b | ADULATION | Tassile: Figlio del Re degl’immortali Numi, A Giove e a Te porto dell’India i Voti. | Taxiles: Son to the King of the immortal Gods, To Jove and thee I bring all India’s Pray’rs. |

| c | PROSTRATION | Cleone: Nato di Giove, sovruman Monarca, Invitto, Augusto, Pio, Sommo, Divino, Con l’Universo a Giove m’inchino. | Cleon: O, born of Jove, chief Monarch of the Earth, Pious, August, Invincible, Divine, To Jove and thee, thus, bowing Worlds incline. |

| d | AVERSION | Clito: (Fremo di rabbia) Io, sol m’inchino a Giove. Tu per sangue e Valor, Re nostro sei. Ti basti ciò: non insultar gli Dei. | Cleitus: (I burn with Rage) I bow alone to Jove: Thou art our King in Valour, and by Blood; Let that suffice thee; nor insult the Gods. |

| e | SURPRISE | Alessandro: Empio, a i Numi negar tenti il rispetto? | Alexander: Would'st, impious, shun Respect to Gods to pay? |

| f | ANGER | Cadi, prostrati, adora a tuo dispetto. | Fall, prostrate, worship, and by Force obey. |

| g | [Clito’s FEAR] | ||

| h | VIOLENT GESTURETERROR | [Lo prostra a forza.] | [He lays him prostrate by force.] |

| i | TERROR | Clito: E ad un’antico tuo Fedel, tal fai Violenza ed inguria? Aless: Empio, superbo, Va altrove ad infuriar. Clito: Ti pentirai. [Parte.] | Cleitus: To one grown old in Loyalty, do you Offer such Violence and such Injustice? Alexander: Thou haughty, impious Wretch; go, rage elsewhere. Cleitus: Most certain you’ll repent it. [Exit.] |

| a | REVERENCE/AWE | Alessandro: Primo motor delle Superne Sfere Da te nato Alessandro umil t’adora Come lor pregio che da te deriva Rendono gli altri Dei; Egli ti rende ancora Tutto l’illustre Onor de’suoi Trofei. | Alexander: Thee, first great Mover of Supernal Spheres, Thy Son, thy Alexander humbly worships; As other Gods, whom all Mankind reveres, Offer the Glories they derive from thee, He pays the Trophies of his Victory. |

| b | ADULATION | Tassile: Figlio del Re degl’immortali Numi, A Giove e a Te porto dell’India i Voti. | Taxiles: Son to the King of the immortal Gods, To Jove and thee I bring all India’s Pray’rs. |

| c | PROSTRATION | Cleone: Nato di Giove, sovruman Monarca, Invitto, Augusto, Pio, Sommo, Divino, Con l’Universo a Giove m’inchino. | Cleon: O, born of Jove, chief Monarch of the Earth, Pious, August, Invincible, Divine, To Jove and thee, thus, bowing Worlds incline. |

| d | AVERSION | Clito: (Fremo di rabbia) Io, sol m’inchino a Giove. Tu per sangue e Valor, Re nostro sei. Ti basti ciò: non insultar gli Dei. | Cleitus: (I burn with Rage) I bow alone to Jove: Thou art our King in Valour, and by Blood; Let that suffice thee; nor insult the Gods. |

| e | SURPRISE | Alessandro: Empio, a i Numi negar tenti il rispetto? | Alexander: Would'st, impious, shun Respect to Gods to pay? |

| f | ANGER | Cadi, prostrati, adora a tuo dispetto. | Fall, prostrate, worship, and by Force obey. |

| g | [Clito’s FEAR] | ||

| h | VIOLENT GESTURETERROR | [Lo prostra a forza.] | [He lays him prostrate by force.] |

| i | TERROR | Clito: E ad un’antico tuo Fedel, tal fai Violenza ed inguria? Aless: Empio, superbo, Va altrove ad infuriar. Clito: Ti pentirai. [Parte.] | Cleitus: To one grown old in Loyalty, do you Offer such Violence and such Injustice? Alexander: Thou haughty, impious Wretch; go, rage elsewhere. Cleitus: Most certain you’ll repent it. [Exit.] |

(a)Alessandro, ‘Primo motor delle superne sfere …’, from Metastasio, Attilio Regolo, scena ultima, in Opere del signor abate Pietro Metastasio (Paris: Herissant, 1780–2), viii, opposite p.5. (The illustrations provided for 18th-century editions of Metastasio's Opere are particularly informative because they match appropriate gestures to specific texts and affective situations.) (b) Tassile, ‘Figlio del Re degl’immortali Numi … ’, from Metastasio, Demetrio, act 3, scene 8, in Opere del signor abate Pietro Metastasio, i, opposite p.215. (The posture of the kneeling figure would be suitable for Tassile, who does not prostrate himself and is thus to be differentiated from the more effusive Cleone (see illus.4c).)

4b

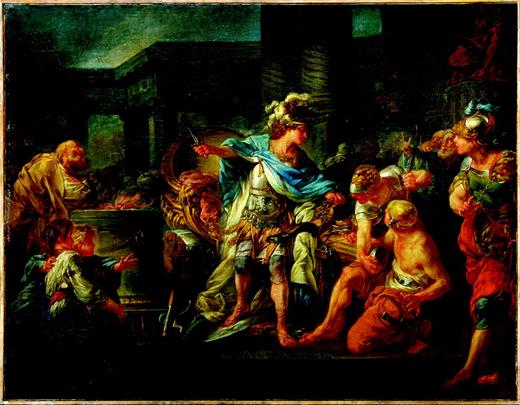

4c Cleone, ‘Nato di Giove … ’, from Jean-Baptiste de Champaigne, Alexander receiving news of the death of the philosopher Calanus (1673) (Salon de Mercure, Versailles). (The figure in the foreground, which is completely prostrated, provides a model for Cleone, who may thus be subtly distinguished from Tassile (illus.4b).)

4d Clito, ‘(Fremo di rabbia)’ (Jelgerhuis, Theoretische lessen (1827), pl.39: contempt)

4e Alessandro, ‘Empio, a i numi negar tenti il rispetto?’ (Jelgerhuis, Theoretische lessen (1827), pl.34: surprise or astonishment)

4f Alessandro, ‘Cadi, prostrati, adora a tuo dispetto’ (Jelgerhuis, Theoretische lessen (1827), pl.32: anger)

4g [Clito’s fear at Alessandro’s mounting anger] (Jelgerhuis, Theoretische lessen(1827), pl.42: fear, terror)

4h ‘(Lo prostra a forza)’ [Alessandro moves to strike Clito down], from Metastasio, Ciro riconosciuto, scena ultima, in Opere del signor abate Metastasio, v, opposite p.113

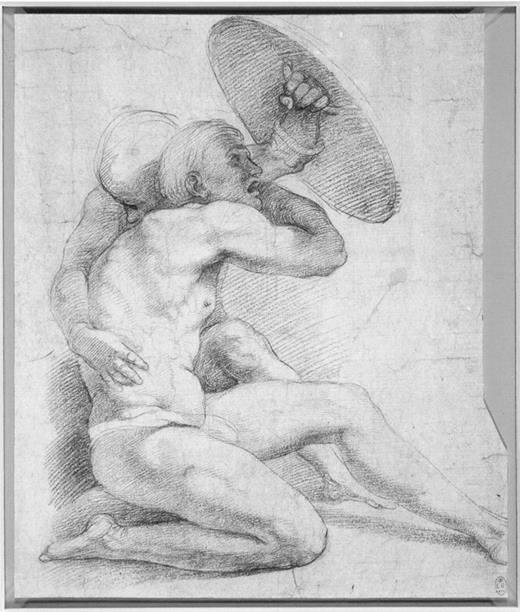

4i Clito, ‘E ad un’antico tuo fedel … ’, Raphael, Two nude figures crouching in terror (study for an alterpiece of the Resurrection, c.1513–14) (Windsor Castle, The Royal Collection: ©HM Queen Elizabeth II)

It seems to me, as it evidently did to David Garrick, that this essentially mechanistic approach misses something.6 It will, of course, work in practically every situation: you can act and sing Caesar, or Scipio or Alexander this way. The problem is that these characters are not interchangeable; they are not simply emblems on the stage, symbols for any and all royalty, or at least they were not, for 18th-century audiences. Each historical figure then conjured up a host of resonances specific to that character. Scipio, for example, was not just a general, but the hero who demonstrated his greatness at least in part through his famous ‘continence’, often represented in 17th- and 18th-century art, and re-enacted in operas such as Handel's Scipione (1726). This specificity was especially true of Alexander the Great, who was not a hero, but the hero—the most glorious of them all.7 It follows that, to perform Alexander, one must understand who he was, and allow that knowledge to guide one's performance.

Two examples will begin to illustrate what this means. Act 1, scene 17 of Aurelio Aureli's arrangement of Giacomo Sinibaldi's Lisimaco riamato d'Alessandro (Venice, 1682; set by Giovanni Legrenzi), begins with Alessandro reflecting upon the actions of his soldiers Lisimaco and Calistene, and then resolving vengeance:

G. Sinibaldi, rev. A. Aureli, Lisimaco riamato d'Alessandro (Venice, 1682), Act 1, scene 17:

| Aless. | Che un Lisimaco altero, | A proud Lisimaco, |

| Un Calistene indegno, | An unworthy Calistene | |

| Alle Grandezze mie tronchi il sentiero; | Should cut short my glories? | |

| Nò, nol deggio soffrir, s’io vivo, e regno; | No, I cannot suffer this, as I live and reign; | |

| Ma dell’ira concetta | But just vengeance shall be | |

| Lenitivo sarà giusta vendetta. | A palliative to my anger. |

| Aless. | Che un Lisimaco altero, | A proud Lisimaco, |

| Un Calistene indegno, | An unworthy Calistene | |

| Alle Grandezze mie tronchi il sentiero; | Should cut short my glories? | |

| Nò, nol deggio soffrir, s’io vivo, e regno; | No, I cannot suffer this, as I live and reign; | |

| Ma dell’ira concetta | But just vengeance shall be | |

| Lenitivo sarà giusta vendetta. | A palliative to my anger. |

| Aless. | Che un Lisimaco altero, | A proud Lisimaco, |

| Un Calistene indegno, | An unworthy Calistene | |

| Alle Grandezze mie tronchi il sentiero; | Should cut short my glories? | |

| Nò, nol deggio soffrir, s’io vivo, e regno; | No, I cannot suffer this, as I live and reign; | |

| Ma dell’ira concetta | But just vengeance shall be | |

| Lenitivo sarà giusta vendetta. | A palliative to my anger. |

| Aless. | Che un Lisimaco altero, | A proud Lisimaco, |

| Un Calistene indegno, | An unworthy Calistene | |

| Alle Grandezze mie tronchi il sentiero; | Should cut short my glories? | |

| Nò, nol deggio soffrir, s’io vivo, e regno; | No, I cannot suffer this, as I live and reign; | |

| Ma dell’ira concetta | But just vengeance shall be | |

| Lenitivo sarà giusta vendetta. | A palliative to my anger. |

Alessandro is angry with the two for spoiling his party earlier in the opera: in a scene reminiscent of Handel's Alessandro (see Table 1), they refused to prostrate themselves before the king, who lost his temper and threw Calistene to the ground, singing words very similar to those set by Handel: ‘Cadi, e adora Alessandro à tuo dispetto’ (Lisimaco riamato d'Alessandro, Act 1, scene 5). We know from history that Alexander was prone to lose his temper, that he was famous for his towering fury; moreover, Sinibaldi portrays the conqueror in a negative light—after his tantrum, Alessandro soon accepts Cleonte's advice that to punish Lisimaco and Calistene, he must ensure that they first lose their honour. This is an ignoble action unworthy of a king. So here, in Aureli's Act 1, scene 17, Alessandro should rage in a manner more extreme than the text alone might suggest.8

A second example concerns Alexander's legendary charisma. The Macedonian's remarkable and instantaneous effect upon those who saw him in person was frequently evoked in 17th- and 18th-century librettos (and plays): his nobility, beauty and so forth were often remarked upon. The next extract, from Aureli's Alessandro magno in Sidone (Venice, 1679; set by M. A. Ziani), presents a typical formulation of this topos. When Alessandro approaches, Eusonia sings:

A. Aureli, Alessandro magno in Sidone (Venice, 1679), Act 2, scene 1:

| Eus. | Ecco Alessandro, ò Cieli. | Here is Alessandro, O Heavens. |

| Che maestà! Che aspetto! | What majesty! What mien! | |

| Chi non l’adora hà un cor di bronzo in petto. | Whoever does not adore him has a heart of stone. |

| Eus. | Ecco Alessandro, ò Cieli. | Here is Alessandro, O Heavens. |

| Che maestà! Che aspetto! | What majesty! What mien! | |

| Chi non l’adora hà un cor di bronzo in petto. | Whoever does not adore him has a heart of stone. |

| Eus. | Ecco Alessandro, ò Cieli. | Here is Alessandro, O Heavens. |

| Che maestà! Che aspetto! | What majesty! What mien! | |

| Chi non l’adora hà un cor di bronzo in petto. | Whoever does not adore him has a heart of stone. |

| Eus. | Ecco Alessandro, ò Cieli. | Here is Alessandro, O Heavens. |

| Che maestà! Che aspetto! | What majesty! What mien! | |

| Chi non l’adora hà un cor di bronzo in petto. | Whoever does not adore him has a heart of stone. |

What others say about the conqueror is just as revealing as what he says or does. Eusonia's choice of language implies that there is more to her fascination with Alessandro than love (in fact, she loves her husband Eumene, though he has betrayed her), or mere beauty: the hero's celebrated charisma is at work. If so, this example suggests that whenever Alexander steps on stage, the singers around him must show the effect of his splendour.9

Of course, we expect kings and conquerors to have this effect; nevertheless, making Alexander’s impact on those around him visible allows us to move from the general to the specific, from the emblematic to the individual.

Modern descriptions of Baroque gesture often seem to suggest a style limited to general, emblematic representations of affect; however, the specific and the individual were also considered essential to good acting then, just as they are today. In a highly regarded acting treatise published in 1710, Charles Gildon stressed their importance, and outlined with such clarity a method for portraying individuality that I must quote him at some length.10

Gildon begins his detailed instructions on acting with a general precept:

With these lines, Gildon hints at a more nuanced approach to acting. It is not enough to understand the passions and know their corresponding gestures. One must also characterize differently their expression by kings and beggars.the action of a player is that, which is agreeable to personation, or the subject he represents … he must perfectly express the quality and manners of the man, whose person he assumes, that is, he must know how his manners are compounded, and from thence know the several features, as I may call ’em, of his passions. A patriot, a prince, a beggar, a clown, &c. must have each their own propriety, and distinction in action as well as words and language. (The Life of Mr Thomas Betterton, pp.33–4)

Gildon then develops this precept in a still more specific manner, suggesting that one must differentiate not only between kings and beggars, but between each and every king:

Each passion has multiple dimensions: Alexander’s anger is a very different thing from Caesar’s, and the actor must understand and convey this difference. How, exactly, shall the actor learn to do this? First, as Gildon suggests above, by reading poetry and history to learn the characters of the heroes he portrays. Second, by studying historical painting, which shows how to depict a subtle mixture of emotions:As [the actor] now represents Achilles, then Aeneas, another time Hamlet, then Alexander the Great and Oedipus, he ought to know perfectly well the characters of all these heroes, the very same passions differing in the different heroes as their characters differ: The courage of Aeneas, for example, of itself was sedate and temperate, and always attended with good nature; that of Turnus join'd with fury, yet accompany'd with generosity and greatness of mind. The valour of Mezentius was savage and cruel; he has no fury but fierceness, which is not a passion but habit, and nothing but the effect of fury cool'd into a very keen hatred, and an inveterate malice. Turnus seems to fight to appease his anger, Mezentius to satisfy his revenge, his malice and barbarous thirst of blood. Turnus goes to the field with grief, which always attended anger, whereas Mezentius destroys with a barbarous joy; he’s so far from fury, that he is hard to be provok’d to common anger; who calmly killing Ondes, grows but half angry at his threats;

At whom Mezentius smiling with a mingl’d Ire.

Thus, ’tis plain, he has not the fury of Turnus, but a barbarity peculiar to himself, and a savage fierceness, according to his character in the tenth book of Virgil.

To know the different characters of established heroes, the actor need only be acquainted with the poets, who write of them. (The Life of Mr Thomas Betterton, pp.35–6)

But to know the different compositions of the manners, and the passions springing from those manners, [the actor] ought to have an insight into moral philosophy, for they produce various appearances in the looks and actions, according to their various mixtures. For that the very same passion has various appearances, is plain from the history painters, who have followed nature. Thus Jordan of Antwerp, in a piece of our Saviour’s being taken from the cross, which is now in his Grace the Duke of Marlborough’s hands, the passion of grief is express’d with a wonderful variety; the grief of the Virgin Mother is in all the extremity of agony, that is consistent with life, nay indeed that leaves scarce any signs of remaining life in her; that of St. Mary Magdalen is an extreme grief, but mingled with love and tenderness, which she always expressed after her conversion for our blessed Lord; then the grief of St. John the Evangelist is strong but manly, and mixt with the tenderness of perfect friendship; and that of Joseph of Arimathea suitable to his years and love for Christ, more solemn, more contracted in himself, and yet forcing an appearance in his looks. Coypel's Sacrifice of Jeptha's Daughter has not unluckily express'd a great variety of this same passion. The history painters indeed have observ'd a decorum in their pieces, which wants to be introduc’d on our stage; for there is never any person on the cloth, who has not a concern in the action. All the very slaves in Le Brun’s Tent of Darius [see illus.14, below] participate of the grand concern of Sisigambis, Statira, &c. (The Life of Mr Thomas Betterton, pp.36–7)

A few pages later, Gildon neatly summarizes all that has been presented above with his assertion that actors ‘must know [the whole nature of the affections, and habits of the mind] in their various mixtures, and as they are differently blended together in the different characters they represent’ (p.40). In other words, this is a two-part equation: know the passions in general; know the character you portray in particular.

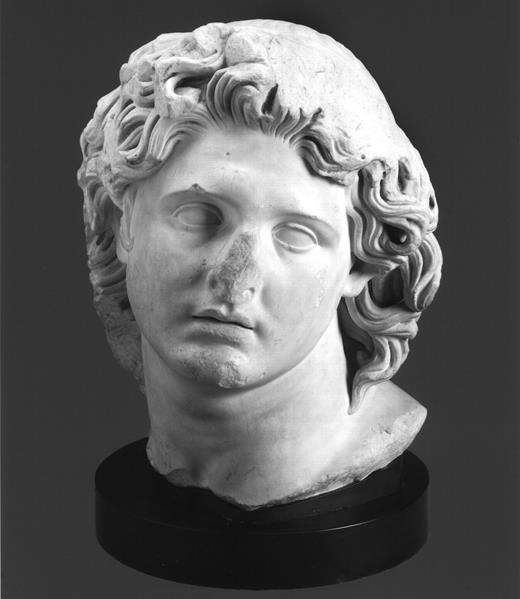

An understanding of who Alexander was is thus a first and essential step towards a resonant portrayal of this famous historical figure. The next step is to answer the inevitable, though less vital, question: what did Alexander look like? For one thing, his hair was tawny and often said to resemble a lion's mane (this is seen in nearly all the ancient likenesses; see, for example, illus.5).11 For another, he was clean shaven, which was considered extraordinary in his time (in fact, Alexander is often prominently featured in accounts of the history of shaving). Thus, he should have no beard—indeed, he can be distinguished from other soldiers on stage by this very feature. Then, there is the famous tilt of his head, which Alexander apparently carried up and to the left (illus.5), and which has been interpreted as an allusion to his divine ancestry.12 It may also have been due to a medical condition: ‘According to the Alexander Romance, his eyes were of different colours. This piece of information, combined with the characteristic twist of the neck and heavenward glance in most of the statues, has been taken as an indication of “ocular torticollis”, a posture of the head which compensates for the palsy of one eye.’13 Whether a result of divine descent or physical handicap, the way Alexander carried himself became in art an emblem of kingship, a topos evident in the portrayals of Greek and Roman rulers for centuries afterwards.

Head of Alexander the Great (c.150–100 BCE) (Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Catharine Page Perkins Fund)

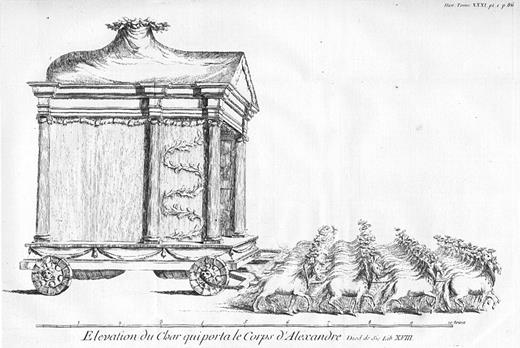

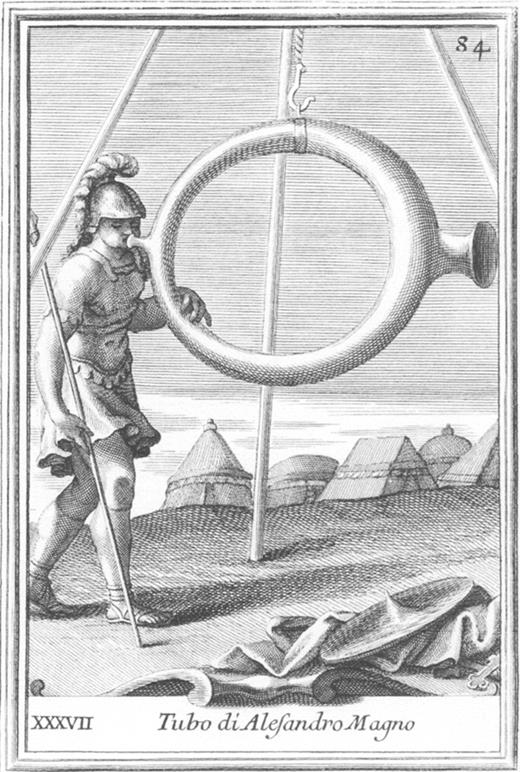

It must be admitted that, while useful, such information concerning Alexander's appearance represents the kind of detail Erkinger Schwarzenberg once mocked as ‘unimportant except for passport identification’.14 Far more essential is an understanding that everything about Alexander was, and still is, larger than life. To illustrate this, we can point in his own time to Alexander’s sarcophagus (illus.6), which is more than 3 metres in length and weighs nearly 15 tons;15 or to his extravagant hearse, which took two years to build and is said to have required 64 mules to pull (illus.7). Later, a host of images conveys this aspect of his posthumous reputation: Alexander’s grandeur is suggested by portrayals of his actions (illus.8), his battles (illus.9), his triumphs (illus.10) and so forth. Even his musical instruments had to be great. Filippo Bonanni’s comically exaggerated Tubo di Alessandro Magno (1723; illus.11) surely says more about Alexander than it does about brass instruments of his time.16 Best of all, perhaps, is Stasikrates’s proposal to transform Mt Athos into what Andrew Stewart has described as ‘a kind of Macedonian Mount Rushmore … The proposed statue, with its feet in the Aegean, its head in the clouds, a city in its left hand, and a libation bowl eternally emptying the rivers of Athos into the sea in its right, is faithfully described by both Vitruvius and Strabo … ’.17 Their descriptions were later given visual form by the 17th-century artist Pietro da Cortona, and, in even grander fashion, by Fischer von Erlach in 1725 (illus.12).18 Plutarch reports Stasikrates as saying Alexander’s left hand would hold a city of 10,000!19 The truth is, Alexander is still larger than life, as the 1993 travel manual cover reproduced as illus.13 suggests: an entire nation, or at least its travel industry, continues to identify itself with the Macedonian.20

Alexander's sarcophagus (c.320–306 BCE) (Istanbul, Archaeological Museum)

Le Compte de Caylus, Alexander's catafalque, in ‘Sur le char qui porta le corps d’Alexandre’, Histoire de l’Académie Royale des inscriptions et belles-lettres, avec les mémoires de littérature tirés des registres de cette académie, depuis l’année M.DCCLXI, jusques & compris l'année M. DCCLXIII, xxxi (Paris, 1768), p.86, pl.1 (Rare Book Collection, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

Jean-Simon Berthelemy, Alexander cuts the Gordian knot(1767) (Paris, École des Beaux-Arts)

Jan Brueghels, The battle of Issus (1602) (Paris, Louvre: ©Réunion des Musées Nationaux)

Sébastien LeClerc, Alexander’s entry into Babylon (1703) (Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Harvey D. Parker Collection)

Filippo Bonanni, Alexander’s trumpet, in Gabinetto armonico pieno d’istromenti sonori (Rome, 1723), pl.37

Johann Bernhardt Fischer von Erlach, Design for a monument to Alexander the Great, in Entwurff einer historischen Architectur, i (Leipzig, 1725), pl.18

How to convey this grandeur is, in my opinion, a question the singer and director must consider. Surely, 17th- and 18th-century librettists, composers, stage and costume designers, and singers did.21 But that question is more difficult today than it was then: because our education differs from theirs, many of us do not really know, as they did, who Alexander was.

A clue as to how Alexander’s magnificence might be manifested on stage is given by Ludovico Castelvetro, in his discussion of the hero or protagonist (Poetica, 1570): ‘nobility or vileness is not to be discerned by [moral] goodness or badness, but by bearing and address: a good deportment is a sign of nobility, an awkward one, of vileness. And by deportment I mean those things which witness not to the moral character but to the courtliness or the boorishness of the hero.’22 Castelvetro leads us back to painting and statuary: to learn how to act Alexander in 17th- and 18th-century operas, we might begin by exploring contemporary French imagery, with its ideally elegant dancers and courtiers. He also suggests how one might play the part of a character such as the sycophant Cleone in Handel’s Alessandro (see Table 1): he should lack grace in both carriage and gesture.

But again, that is an emblematic as opposed to individual approach. The way forward, it seems to me, is to take seriously what Gildon and the authors of many other acting treatises tell us: actors and singers, like historical painters, must study ancient and modern art, and emulate the gestures they find there.23 What is needed is a model for how to do this, and that is what I propose to sketch in the following part of this article.

Even the most cursory study of Baroque gesture reveals a long and close relationship between the plastic arts and the stage. Each was influenced by the other: actors modelled at least some of their gestures on those found in painting and statuary; painters used actors as inspiration for their own ideas of gesture.24 Both shared the preoccupation with antiquity characteristic of their time.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Greek and Roman literature was painstakingly parsed for information on everything from the nature and structure of tragedy to personal conduct in society. Antique art was of equal interest, and equally accessible. The nobility collected classical art, and often made their collections available to artists, who copied from them, and others, who simply admired them. In addition, numerous publications reproduced the celebrated art works of antiquity, and thus made them accessible to a still wider audience.25 This means that images of Alexander, one of the central figures in antiquity, were widely available.

An understanding of who Alexander was (and thus of the significance and meanings of the historical events re-enacted on stage), together with knowledge of the acting method outlined above (based on study and emulation of ancient and modern art), can lead us, like 17th- and 18th-century performers and designers, to suitable model images for acting and staging operas in which Alexander appears, images that surely would have been recognized by Handel or Hasse, and their audiences. For example, fitting postures for the scene in Handel’s Alessandro in which Rossane asks for and receives her freedom from the conqueror (Act 2, scene 4) are seen in Charles Le Brun’s painting The tent of Darius (illus.14). In the famous incident depicted there, Alexander similarly restored the captive family of the defeated Persian king to their former status. Le Brun’s portrayal of this episode was widely transmitted through tapestries and engravings, often cited in literature, and frequently imitated by artists in 18th-century England; moreover, his Alexander paintings had already been used on London’s stages, notably, for a King’s Theatre production in 1717 of the pasticcio opera Clearte, possibly conducted by Handel himself.26

Charles Le Brun, The tent of Darius (1660–1) (Versailles, Château de Versailles: ©Réunion des Musées Nationaux)

Another staging inspiration, in this case for the scene given as Table 1, is provided by John Devoto’s 1724 drawing of a temple similarly dedicated to Jupiter (illus.15).27 The design is reminiscent of the frontispiece temple of a 17th-century edition of Arrian’s Alexander biography (the Anabasis), in which both the practice and the problem of prostration are illustrated (illus.16).28 Aside from Alexander, two groups differentiated by dress are represented: Persians in flowing robes prostrate themselves to the conqueror, while helmeted Macedonian soldiers, evidently displeased with the proceedings, stand around grumbling (to the left). A modern production of Handel’s scene might use Devoto’s contemporary design for the setting, and arrange singers and supernumeraries in the manner seen in the earlier Anabasis frontispiece.

John Devoto, Design for a temple dedicated to Jupiter (1724) (London, British Museum: ©The Trustees of the British Museum)

Arrianou Peri Anabaseos Alexandrou (Amsterdam, 1668), frontispiece (Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries)

For an historically oriented performance of Handel’s Alessandro and other operas in which that king appears, I would suggest the singer portraying Alexander at least occasionally carry himself with his head cocked as Alexander’s was, according to the historians. Handel’s English contemporaries revelled in the knowledge of historical detail,29 and there are several mentions of Alexander’s ‘nod’ in journals and other sources of the time.30 Moreover, as we have seen (illus.5), this is how he was typically represented, and not only in antiquity: the tilt (or, at least, a head clearly oriented towards the left shoulder) is clear in all five of Le Brun’s celebrated Battles [or Triumphs] of Alexander paintings.

What I am trying to show, by way of a very small sample, is that it is essential to immerse oneself not only in the literature, but also, and more vitally, in the iconography of Alexander to portray him convincingly. We understand the world through our senses, and it has long been observed that of these, the visual—what we see—is most persuasive. Careful study of Alexander imagery helps us, in a way impossible to define with words, better to understand what he meant then, and what he might mean now.

Conclusion

My goal in this essay has been to develop a broad view of what it means ‘to be an emperor’ on the opera stage. This is, in part, a ‘how-to’, but, as I hope is clear, I am less interested in directions such as ‘here’s where you extend your arms and express horror’ (admittedly, an essential first step), than I am in how to bring a king such as Alexander the Great to life today, to make him meaningful now and at the same time preserve what he meant then; or, at least, to let what he was then shape how we represent him today.

This interest inevitably leads to difficult questions. Can we expect singers or directors to do such research; to study ancient history and portraiture, 17th- and 18th-century criticism and paintings? Probably not. What I’m asking for sounds like work for the scholar. And even if scholars do win performers over, what about audiences? How can we educate them to appreciate what they see on stage if directors and singers adopt this approach? No doubt each production of this type will require extensive programme notes, outlining the sources and the rationale behind the art, explaining the meanings of the various scenes and so forth.

Finally, we are all aware (or at least we have all been told) that historical exactness has little value in and of itself.31 That does seem to be what artists say. Think of the countless illustrations of religious and historical events in medieval manuscript illuminations and Renaissance paintings (to say nothing of representations of Alexander in the East) that present their characters in contemporaneous settings and costumes. The past serves the present, and thus in his celebrated and censured productions of operas and oratorios by Handel and Mozart, Peter Sellars was simply doing what artists do. But if not historical exactness, then what? That is, how might we bring Alexander to life in our productions of Baroque opera today while preserving what he meant to the original creators and audiences of those operas? In this article, I have suggested a tentative answer to that question. One thing is certain: the question itself is well worth asking. Why? As Philip Brett put it, an historical approach to performance can give us ‘a sense of difference, a sense that by exercising our imaginations we may, instead of reinforcing our own sense of ourselves by assimilating works unthinkingly to our mode of performing and perceiving, learn to know what something different might mean and how we might ultimately delight in it’.32

An earlier version of this essay was read at the Sixth Triennial Conference of the Handel Institute (London) in November 2005. I thank the University of Maryland's General Research Board for a Semester Research Grant that enabled me to complete this article.

R. Strohm, ‘Towards an understanding of the opera seria’, in Essays on Handel and Italian opera (Cambridge, 1985), p.98.

Though not, apparently, entirely ephemeral: in 1755 Francesco Algarotti noted that the French still remembered the original actors of the plays of Corneille and Racine and kept in mind the ‘superior strokes of art’ of those actors in their own performances; he suggested that Italians would do well similarly to remember and emulate Nicolini and Tesi. An Essay on the Opera Written in Italian by Count Algarotti F.R.S. F.S.A. etc. (London, 1767), pp.53–4. England also had a long tradition of actors performing tragic parts in perfect imitation of their predecessors. See L. B. Campbell, ‘The rise of a theory of stage presentation in England during the eighteenth century’, Proceedings of the Modern Language Association, xxxii (1917), pp.163–200, esp. pp.163–7.

D. Barnett, The art of gesture: the practices and principles of eighteenth-century acting (Heidelberg, 1987). A useful summary of the basics is provided by N. Solomon, ‘Signs of the times: a look at late 18th-century gesturing’, Early Music, xvii (1989), pp.551–62. For a different perspective on this ‘traditional’ acting style, see G. W. Stone, Jr. and G. M. Kahrl, David Garrick: a critical biography (Carbondale, 1979), pp.27–36.

Solomon, ‘Signs of the times’, p.552; see also Barnett, The art of gesture, pp.368–76.

Solomon, ‘Signs of the times’, pp.552, 554.

For Garrick’s revolution in acting technique, see Stone and Kahrl, David Garrick, pp.28–9, 36–51.

See R. G. King, ‘Classical history and Handel’s Alessandro’, Music & Letters, lxxvii (1996), p.38.

Unfortunately, the music for these recitatives does not survive. See The New Grove dictionary of opera, ed. S. Sadie and C. Bashford (London, 1992), ii, p.1128. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that Legrenzi marked these events by setting the texts as anything other than simple recitative.

Gildon's observations form part of his The Life of Mr. Thomas Betterton, the Late Eminent Tragedian (London, 1710/R1970).

The ancient portraits are all reproduced in A. Stewart, Faces of power: Alexander's image and Hellenistic politics (Berkeley, 1993).

A. Fildes and J. Fletcher, Alexander the Great: son of the gods (Los Angeles, 2001), p.108.

R. Stoneman, Alexander the Great (London and New York, 1997), p.15.

‘The portraiture of Alexander’, in Alexandre le grand: image et réalité, Entretiens sur l’antiquité classique, xxii (Geneva, 1976), p.227.

Stewart, Faces of power, p.294.

According to Frank Ll. Harrison and Joan Rimmer, Bonanni took this image from Athanasius Kircher, who said he found it in a Vatican Library manuscript. See Antique musical instruments and their players: 152 plates from Bonanni’s 18th century ‘Gabinetto Armonico’, with a new Introduction and captions by F. Ll. Harrison and J. Rimmer (New York, 1964), pl.37. I have not traced the image described by Kircher, but he does discuss the loud and unusual sound of Alexander’s trumpet in his Musurgia Universalis (Rome, 1650/R1970), ii, pp.274–5. I thank Barbara Haggh-Huglo for translating Kircher’s comments.

Stewart, Faces of power, p.28.

Stewart (Faces of power, pp.402–7) reprints and translates the ancient texts concerning this proposed tribute to Alexander. Pietro da Cortona’s drawing is reproduced in The search for Alexander: an exhibition (Washington, DC, 1980), p.19.

Plutarch, De Alexandri Magni fortuna aut virtute 2.2–3.1, Life of Alexander, p.72; translated by Stewart, Faces of power, pp.404, 405.

I thank Caterina Pizanias for bringing this manual to my attention.

See R. G. King, At play with history: Alexander the Great in seventeenth- and eighteenth century culture (forthcoming).

O. L. Brownstein and D. M. Daubert, Analytical sourcebook of concepts in dramatic theory (Westport, CT, and London, 1981), p.191. See also Barnett, The art of gesture, pp.137–8; and Gildon, The Life of Mr Thomas Betterton, pp.33–4 (quoted above).

See Barnett, The art of gesture, p.127; and also the citations from 18th-century sources in A. S. Downer, ‘Nature to advantage dressed: eighteenth-century acting’, Proceedings of the Modern Language Association, lviii (1943), p.1028. For historical painters, see J. Locquin, La peinture d’histoire en France de 1747 à 1785 (Paris, 1912), especially part II.

See A. Goodden, Actio and persuasion: dramatic performance in eighteenth-century France (Oxford, 1986), ch.3.

J. E. Schloder, Baroque imagery (exhibition catalogue 6 November 1984–6 January 1985) (Cleveland Museum of Art, 1984), p.48. Asa Briggs notes that, ‘During the middle and late eighteenth century there was great enthusiasm [in England] for collecting pictures, statuary and antiquities from Europe, particularly Italy … English artists at Rome made money by buying, restoring and selling ancient “masterpieces”.’ How they lived, volume iii: an anthology of original documents written between 1700 and 1815 (New York, 1969), p.430.

For Clearte, performed on 30 March 1717, one of the scenes was advertised as, ‘a room adorned with tapestry, representing the famous Battles of Alexander by Mons le Brun’. Later that year, Le Brun’s paintings figured in the performance of another stage work, The maid’s tragedy (Drury Lane, 12 October 1717), for which an advertisement reads: ‘With a new set of scenes, after Le Brun’s Battle of Alexander’. See The London stage 1660–1800, ed. W. van Lennep et al. (Carbondale, 1960–65), pt. II, i, pp.443, 464. Clearte, adapted by Nicolini from Alessandro Scarlatti’s L’amor volubile e tiranno, was in rotation at the King’s Theatre in 1717 with Handel’s opera Amadigi di Gaula, which featured Nicolini in the title role (Amadigi was performed on 21 March and 11 April; Clearte on 30 March). Nicolini sang in the production of Clearte that featured Le Brun’s ‘Battles of Alexander’, and therefore, at least theoretically, could not lead the orchestra. It is thus possible, indeed likely, that Handel directed that performance from the harpsichord—it is more than likely that he at least saw this production featuring Le Brun’s designs. For information on Clearte and the dates of the Amadigi performances, see W. Dean and J. Merrill Knapp, Handel’s operas, 1704–1726 (Oxford, 1987), p.162 and Appendix C.

The temple of Jupiter is the scene of extended passages in the first and third acts of Handel’s Alessandro. Lowell Lindgren hypothesizes that Devoto may have provided designs for some of Handel’s operas. ‘The staging of Handel’s operas in London’, in Handel tercentenary collection, ed. S. Sadie and A. Hicks (London, 1987), pp.102–12.

Arrianou Peri Anabaseos Alexandrou (Amsterdam, 1668). Alexander attempted to introduce among his soldiers the Persian practice of proskynesis, or prostration, which required those who came into the king's presence to prostrate themselves before him. The problem was that for Macedonians this act implied worship of a god. The prostration became a sore point between Alexander and his men, and a factor in revolts against his leadership.

In The Tatler, lxviii (15 September 1709), Richard Steele wrote: ‘There is nothing can so much contribute to create a noble emulation in our youth, as the honourable mention of such whose actions have outlived the injuries of time, and recommend themselves so far to the world, that it is become learning to know the least circumstance of their affairs’ (my emphasis).

See The Tatler, lxxvii (4 October 1709); The Spectator, xxxii (14 April 1711). André Felibien praised the way Lebrun exploited this physical characteristic in his painting of the Tent of Darius episode. See Les Reines de Perse aux pieds d’Alexandre (Paris, 1663), trans. Colonel Parsons as The Tent of Darius Explain’d; or the Queens of Persia at the Feet of Alexander (London, 1703), p.13.

As Richard Taruskin famously pointed out some 25 years ago. See his Text and act: essays on music and performance (New York and Oxford, 1995). Reinhard Strohm was clearly saying the same thing at about the same time (see the quotation at the beginning of this article).

‘Text, context, and the early music editor’, in Authenticity and early music: a symposium, ed. N. Kenyon (Oxford and New York, 1988), p.114.